A Conductor of Partnerships: Dr. Tom Nevill on Innovation and Apprenticeships at GateWay Community College

Located in the metropolis of Phoenix, Arizona, GateWay Community College is at the center of both growing industries and a growing population.

Almost any higher ed administrator will tell you that making major changes at an institution without faculty support makes the initiative substantially harder to get across the finish line. As higher ed faces greater pressures, faculty are increasingly asked to help support both institutional growth and student success. However, creating a productive and trusted relationship with faculty takes time and effort.

Dr. Rachel Winslow, Director of Faculty Development and Associate Professor of History at George Fox University, offers insight into her role working with faculty as well as lessons administrators can use to work with faculty on meaningful change.

George Fox University, a four-year private institution in Newberg, OR boasts nearly 200 full-time faculty as well as part-time instructors. To support this large group, Dr. Winslow engages faculty in a number of areas including professional development, new faculty onboarding, and serving as a dedicated resource for teaching, learning, and growth. Dr. Winslow shared what she has learned from this work and her unique approach to faculty advocacy and development.

At the heart of it, “The role was designed so that the faculty had a faculty. A person to go to who was going to be invested in their interests in promotion and tenure, onboarding for new faculty, and a resource for teaching and learning,” Dr. Winslow explains. This unique role gives her insight into what faculty value, how they can best be supported, and how academic operations professionals can partner with faculty to achieve results.

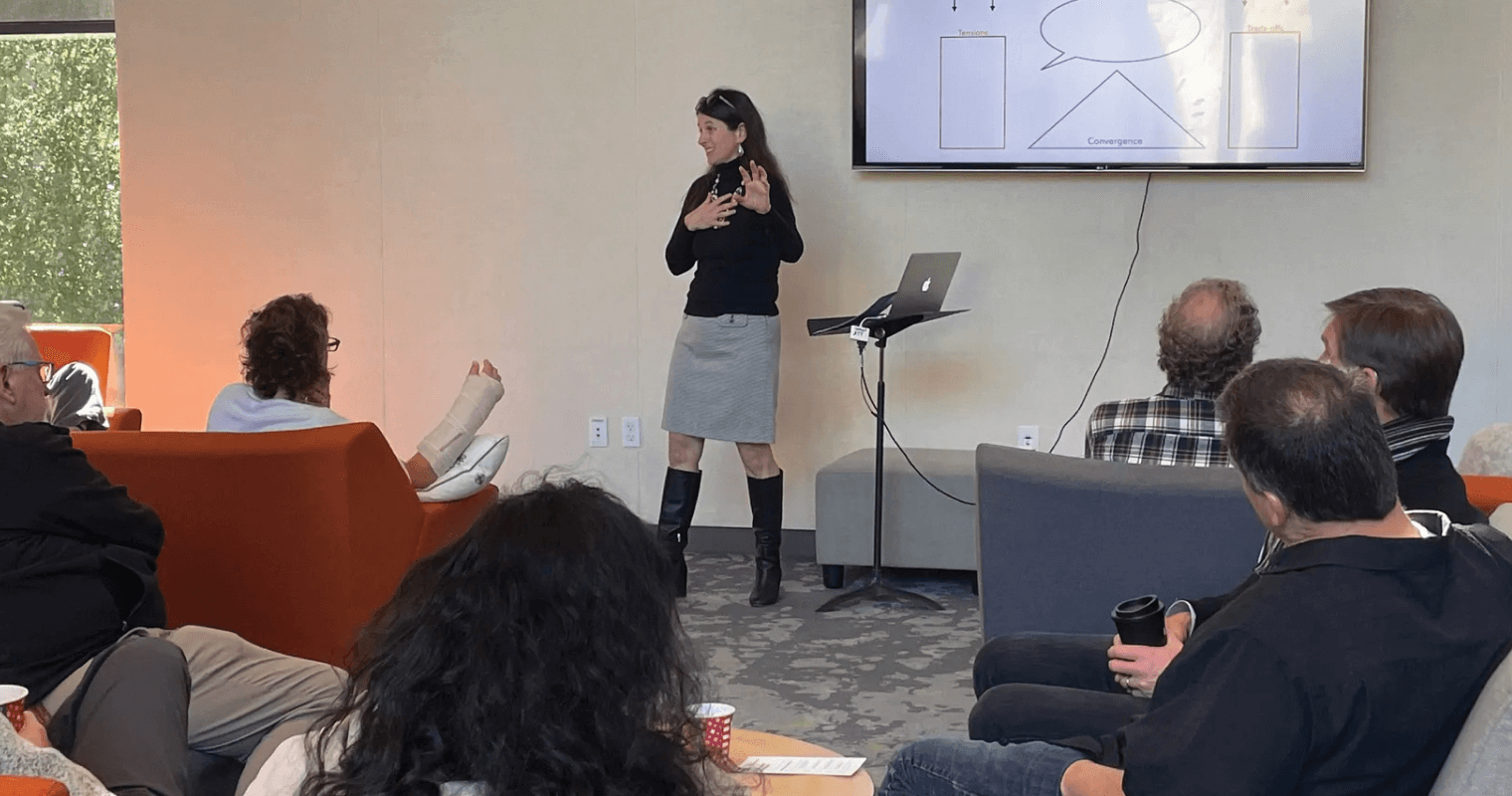

One of the first steps toward gaining faculty buy-in is to include them in setting the direction for major institutional initiatives. Dr. Winslow shares an example of an undergraduate faculty conference she hosted, which used “open space technology and design” to empower faculty to set the agenda. Instead of dictating the terms of the agenda, this innovative approach allowed for organic discussions that directly addressed faculty concerns and interests. “Rather than having administrators shape the agenda, and how things were talked about, and what people were going to do, faculty got to shape what the agenda was,” Dr. Winslow recounts.

What does this look like in practice? During the conference, faculty were asked to share actionable ideas on student retention. Dr. Winslow posed questions such as “Where are you already working? What do you already care about? How can we find the threads that link what you’re already doing to student retention outcomes?” The discussion led to tangible retention strategies focused on the first-year experience and peer mentorship. This collaborative spirit, she notes, resonated deeply with faculty who are inherently invested in student well-being. “One of the things that is missionally unifying at George Fox is the fact that they really do care about students.”

The impact of this approach has already shown strong results in the past year. George Fox University saw its student retention rate improve from 78% to 82% in the last academic year. Dr. Winslow attributes this success to the power of faculty-student relationships. “All of our data from exit interviews with students suggests that a crucial relationship with a faculty member makes a difference for a student. When students feel like they belong, they stay, and they succeed,” she notes.

While any major initiative will likely consult data to help inform decision-making, Dr. Winslow offers a cautionary piece of advice to administrators: relying solely on data for decision-making can be a pitfall. She explains that research shows that human decisions are not purely rational and are influenced by other factors such as values, emotions, and relationships. Therefore, discussions should be framed around shared values and the “wisdom of the crowd” should be embraced through group-based discussions to integrate multiple perspectives. She advises that administrators trained in facilitation skills can greatly improve trust and collaboration when working with faculty.

Dr. Winslow warns against a common misstep that she often sees—administrators asking for faculty input without a genuine intention to incorporate it. Treating feedback as just a checkbox, she warns, erodes trust. “I’ve watched administrators come into a space and say, ‘Hey, faculty, I’m really interested in what you think.’ And they listen. And then 30 minutes later, they’re like, ‘Okay, so we’re going to do this.’” This rush to efficiency, she argues, ultimately backfires, alienating faculty and leading to unsustainable decisions.

In Dr. Winslow’s experience, leaders may be drawn to the allure of efficiency over consensus. However, she cautions that, “If you haven’t brought your community alongside with you, that decision, the second that you’re out of that position or something else changes outside of your control, that decision’s lost. It’s gone.”

Dr. Winslow is no stranger to conflict management. Aside from her work as a faculty advocate and liaison, she also works with organizations in the public sector and religious communities on conflict management and consensus building. This work continues to show Dr. Winslow time and time again the value of collaborative processes over rushing to outcomes.

So, how can academic operations leaders meaningfully collect feedback and build consensus? Dr. Winslow advocates for a three-pronged approach: engage faculty in the decision-making processes, acknowledge underlying tensions, and use conflict as an opportunity to address core issues. She personally used this approach at George Fox when they revised the faculty handbook. The eight-month, iterative process involved both faculty and the board, but ultimately culminated in near-unanimous support. This deliberate approach, she explains, allows for a deeper understanding of the “divergence that must exist in any decision we’re willing to live with.” She adds, “When I hear just convergence at the beginning, I’m automatically suspicious. I don’t believe it.”

Essentially, convergence at the beginning of any hot-topic conversation often means stakeholders may not be comfortable sharing their views or one viewpoint is dominating the discussion. She reminds us that “faculty are not a homogeneous entity.” Recognizing the multitude of viewpoints and interests within the faculty community is necessary to identify points of contention, productively talk through them, and then arrive at a decision.

Dr. Winslow’s extensive experience in conflict management across various sectors underscores that fostering open dialogue, even amidst disagreement, leads to sustainable change that supports institutional progress. By actively engaging faculty in decision-making, acknowledging differing perspectives, and reframing conflict as an opportunity for deeper understanding, academic operations leaders can cultivate the buy-in necessary to address complex challenges and better support students.